Have you ever wondered why our gluteal muscles, particularly the gluteus maximus, are so large and powerful compared to those in other animals? The reason is straightforward and lies in our unique bipedal locomotion system: we stand and move on two legs!

Walking on two legs instead of four necessitates strong and powerful gluteal muscles for optimal functionality. When our gluteal muscles aren't adequately activated, we lose much of our core stability, increasing the risk of various injuries. These injuries can affect the back, hips, and the entire lower extremity, including knees, ankles, and feet.

Article Index:

Gluteal Muscle Anatomy & General Function

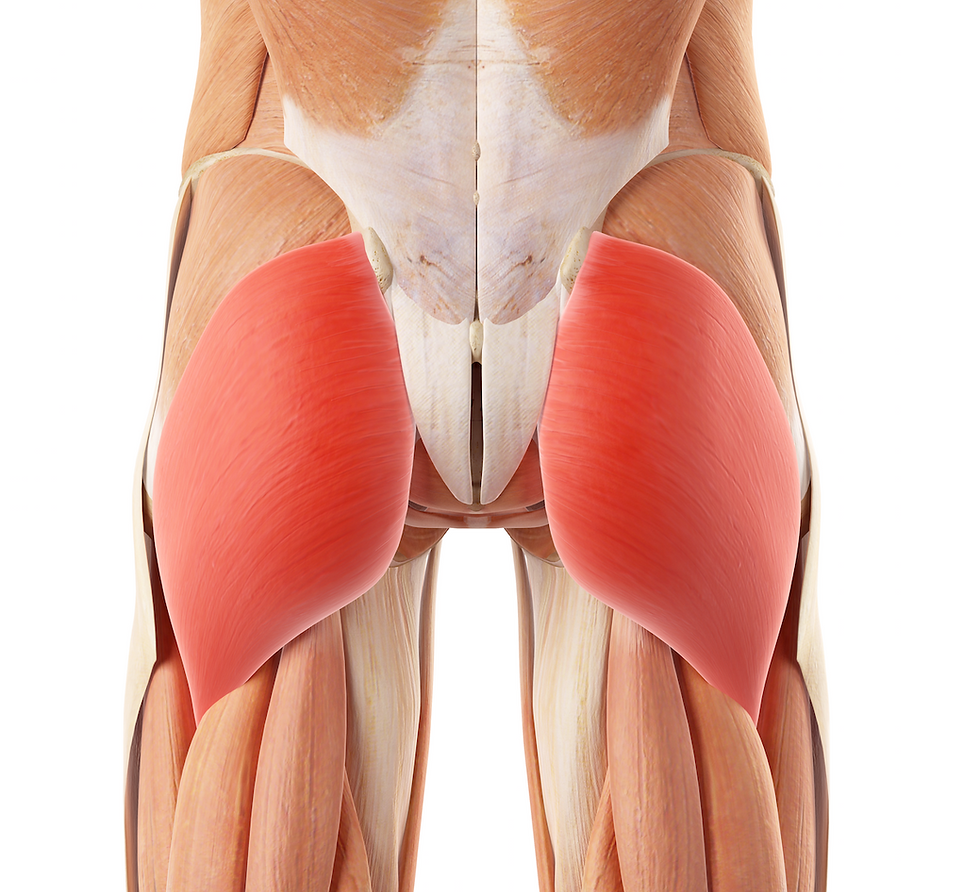

The gluteal region consists of three key muscles: gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus.

Gluteal muscles serve various essential functions:

Act as primary hip extensors, external rotators, and shock absorbers by eccentrically dissipating force.

Stabilize the hip by counteracting gravity's hip adduction torque.

Stabilize the sacroiliac joint.

Maintain proper leg positioning by eccentrically controlling internal rotation and adduction of the leg.

Play a significant role in pelvic and spinal stabilization.

Maintaining an upright posture by balancing the pelvis on the femoral head greatly influences overall posture.

Provide stability to the knees, ankles, and feet, acting as a crucial component in the kinetic chain from your feet to your core.

Gluteal Amnesia

In a world where sedentary lifestyles prevail, biomechanical experts are raising awareness of 'gluteal amnesia,' a condition caused by excessive sitting.

Extended periods of sitting result in shortened, tightened hip flexors (iliopsoas). Since hip flexors act as antagonists to the glutes (gluteus maximus), their contraction neurologically hinders gluteal functionality. Similarly, tightened adductor muscles on the inner thighs impede the gluteus medius muscle.

This impaired gluteal function compromises core and lower body stability, manifesting in several ways. Weakened glutes lead to increased internal rotation of the leg (femur), which causes inward knee movement (knee valgus) and excessive foot pronation. The inward knee movement notably heightens the risk of ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) injuries. Furthermore, excessive pronation is linked to knee, ankle, and foot problems. Research also highlights a correlation between hip muscle strength and chronic ankle sprains (8). Plantar fasciitis is yet another issue associated with excessive pronation.

Gluteal Function & Running

Optimal running performance relies on strong, flexible, and engaged gluteal muscles. These muscles significantly influence our gait patterns. Let's explore the primary roles the Gluteus Maximus and Gluteus Medius play in a runner's gait.

The Gluteus Maximus Muscle

Let's discuss the Gluteus Maximus (G-Max) muscle (shown in red). The Gluteus Maximus muscle (1,2):

It is highly active at the beginning of the stance phase and the end of the swing phase in running gait, which indicates its crucial role in stabilization and propulsion.

Initiates hip extension and decelerates hip flexion. Interestingly, we typically associate the Gluteus Maximus with hip extension, yet it's most active during thigh flexion (as shown by EMG analysis). One of the G-Max's key functions is controlling hip flexion, which might be counterintuitive initially.

Contributes to hip and knee stability during foot contact and mid-stance phases of gait.

Helps limit subtalar joint pronation. Excessive subtalar joint pronation has been linked to knee issues, such as patellofemoral dysfunction.

Clinical Tip: A weak Gluteus Maximus results in a backward trunk lurch upon heel strike. This can be observed during gait analysis with practice.

The Gluteus Medius Muscle

The Gluteus Medius muscle (G-Med) (3,4):

It is highly active at the beginning of the stance phase and the end of the swing phase in a runner's gait. This indicates the gluteus medius plays a crucial role as a frontal plane stabilizer.

Distributes force throughout the hip joint during the stance phase of running. A strong gluteus medius helps protect the hips by ensuring proper force distribution and stabilization.

Clinical Tip: The Trendelenburg Gait – If a runner has a weak gluteus medius, you'll notice a hip drop during the stance phase of their gait. This hip drop will occur on the opposite hip of the foot touching the ground (5,6). This can be observed during gait analysis with practice.

Addressing Gluteal Restrictions

A wide range of approaches can be used to address restrictions in the gluteal muscles. Each case of gluteal restriction should be assessed and treated as a unique dysfunction specific to the individual. Some cases may only involve local structures (gluteus medius, maximus, or minimus muscles), while others may involve a more extensive kinetic chain (psoas, hamstrings, or adductor muscles).

The video below demonstrates some procedures for releasing restrictions in the Gluteus Maximus muscle. Often, treating the Gmax is combined with addressing other structures in a larger kinetic chain, including osseous structures.

Gluteus Maximus Release - (MSR):

In this video Dr. Abelson demonstrates how to use Motion Specific Release (MSR) to release restrictions in the Gluteus Maximus muscle. Strong, flexible, engaged gluteal muscles are critical to optimum performance and injury prevention.

Mobilizing the Hip Joint - Motion Specific Release

Hip mobility is a key aspect of your bodies Kinetic Chain. Since no joint operates in isolation, a lack of hip mobility will affect your knees, ankles, lower back, and upper extremities. The hip joint is a ball-and-socket synovial joint designed to allow multiaxial motion while transferring load between the upper and lower extremities.

Gluteal Exercises

Activating your gluteal muscles is crucial for injury prevention and enhancing athletic performance.

We recommend the following sequence of exercises for patients. Begin by focusing on flexibility and myofascial release exercises for a few weeks. Then, introduce strengthening exercises into your routine. Finally, work on balance and proprioception to engage more of your nervous system.

Some of the most effective exercises for gluteal activation include single-leg squats and single-leg deadlifts.

Flexibility & Myofascial Release Exercises

Strengthening Exercises

Balance Exercises

Conclusion

Understanding the crucial role that our gluteal muscles play in our unique bipedal locomotion system is essential. The gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus are not just about aesthetics; they are vital for maintaining core stability, supporting our posture, and preventing injuries. When these muscles are not adequately activated, it can lead to various injuries affecting the back, hips, knees, ankles, and feet. Therefore, addressing gluteal restrictions and incorporating targeted exercises is pivotal for overall musculoskeletal health and functionality.

In conclusion, manual therapy and targeted exercises for the gluteal muscles can significantly improve the management and prevention of lower extremity injuries. By focusing on strengthening, mobilizing, and maintaining the flexibility of these muscles, we can enhance our core stability and overall movement efficiency. The techniques and exercises discussed in this article offer a comprehensive approach to activating and maintaining gluteal muscle health, thereby improving the quality of life and athletic performance for individuals of all activity levels.

References

Lieberman, D. E., Raichlen, D. A., Pontzer, H., Bramble, D. M., & Cutright-Smith, E. (2006). The human gluteus maximus and its role in running. Journal of Experimental Biology, 209(11), 2143-2155.

Semciw, A. I., Pizzari, T., & Murley, G. S. (2013). Gluteus medius: an intramuscular EMG investigation of anterior, middle and posterior segments during gait. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 23(4), 858-864.

Neumann, D. A. (2010). Kinesiology of the hip: A focus on muscular actions. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(2), 82-94.

Wilson, N. A., Press, J. M., Koh, J. L., Hendrix, R. W., & Zhang, L. Q. (2009). In vivo noninvasive evaluation of abnormal patellar tracking during squatting in patients with patellofemoral pain. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 91(3), 558-566.

Nadler, S. F., Malanga, G. A., DePrince, M., Stitik, T. P., & Feinberg, J. H. (2000). The relationship between lower extremity injury, low back pain, and hip muscle strength in male and female collegiate athletes. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 10(2), 89-97.

Delp, S. L., Hess, W. E., Hungerford, D. S., & Jones, L. C. (1999). Variation of rotation moment arms with hip flexion. Journal of Biomechanics, 32(5), 493-501.

Kim, C., Linsenmeyer, K. D., & Vlad, S. C. (2014). Prevalence of radiographic and symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in an urban United States community: the Framingham osteoarthritis study. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 66(11), 3013-3017.

Friel, K., McLean, N., Myers, C., & Caceres, M. (2006). Ipsilateral hip abductor weakness after inversion ankle sprain. Journal of Athletic Training, 41(1), 74-78.

Neumann, D. A. (2012). Kinesiology of the musculoskeletal system: foundations for rehabilitation. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Janda, V. (1987). Muscles and motor control in low back pain: Assessment and management. In Physical Therapy of the Low Back (pp. 253-278). Churchill Livingstone.

Powers, C. M. (2010). The influence of abnormal hip mechanics on knee injury: a biomechanical perspective. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(2), 42-51.

Grimaldi, A., Richardson, C., Stanton, W., Durbridge, G., Donnelly, W., & Hides, J. (2009). The association between degenerative hip joint pathology and size of the gluteus maximus and tensor fascia lata muscles. Manual Therapy, 14(6), 611-617.

Distefano, L. J., Blackburn, J. T., Marshall, S. W., & Padua, D. A. (2009). Gluteal muscle activation during common therapeutic exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 39(7), 532-540.

Fredericson, M., & Moore, T. (2005). Muscular balance, core stability, and injury prevention for middle-and long-distance runners. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics, 16(3), 669-689.

Willson, J. D., & Davis, I. S. (2008). Lower extremity mechanics of females with and without patellofemoral pain across activities with progressively greater task demands. Clinical Biomechanics, 23(2), 203-211.

Ireland, M. L., Willson, J. D., Ballantyne, B. T., & Davis, I. M. (2003). Hip strength in females with and without patellofemoral pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 33(11), 671-676.

Safran, M. R., Garrett, W. E., Seaber, A. V., Glisson, R. R., & Ribbeck, B. M. (1988). The role of warmup in muscular injury prevention. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 16(2), 123-129.

O'Sullivan, K., Smith, S. M., & Sainsbury, D. (2010). Electromyographic analysis of the three subdivisions of gluteus medius during weight-bearing exercises. Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation, Therapy & Technology, 2(1), 17.

Worrell, T. W. (1994). Factors associated with hamstring injuries. An approach to treatment and preventative measures. Sports Medicine, 17(5), 338-345.

Disclaimer:

The content on the MSR website, including articles and embedded videos, serves educational and informational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice; only certified MSR practitioners should practice these techniques. By accessing this content, you assume full responsibility for your use of the information, acknowledging that the authors and contributors are not liable for any damages or claims that may arise.

This website does not establish a physician-patient relationship. If you have a medical concern, consult an appropriately licensed healthcare provider. Users under the age of 18 are not permitted to use the site. The MSR website may also feature links to third-party sites; however, we bear no responsibility for the content or practices of these external websites.

By using the MSR website, you agree to indemnify and hold the authors and contributors harmless from any claims, including legal fees, arising from your use of the site or violating these terms. This disclaimer constitutes part of the understanding between you and the website's authors regarding the use of the MSR website. For more information, read the full disclaimer and policies in this website.

DR. BRIAN ABELSON DC. - The Author

Dr. Abelson is dedicated to using evidence-based practices to improve musculoskeletal health. At Kinetic Health in Calgary, Alberta, he combines the latest research with a compassionate, patient-focused approach. As the creator of the Motion Specific Release (MSR) Treatment Systems, he aims to educate and share techniques to benefit the broader healthcare community. His work continually emphasizes patient-centered care and advancing treatment methods.

Join Us at Motion Specific Release

Enroll in our courses to master innovative soft-tissue and osseous techniques that seamlessly fit into your current clinical practice, providing your patients with substantial relief from pain and a renewed sense of functionality. Our curriculum masterfully integrates rigorous medical science with creative therapeutic paradigms, comprehensively understanding musculoskeletal diagnosis and treatment protocols.

Join MSR Pro and start tapping into the power of Motion Specific Release. Have access to:

Protocols: Over 250 clinical procedures with detailed video productions.

Examination Procedures: Over 70 orthopedic and neurological assessment videos and downloadable PDF examination forms for use in your clinical practice are coming soon.

Exercises: You can prescribe hundreds of Functional Exercises Videos to your patients through our downloadable prescription pads.

Article Library: Our Article Index Library has over 45+ of the most common MSK conditions in clinical practice. This is a great opportunity to educate your patients on our processes. Each article covers basic condition information, diagnostic procedures, treatment methodologies, timelines, and exercise recommendations. This is in an easy-to-prescribe PDF format you can directly send to your patients.

Discounts: MSR Pro yearly memberships entitle you to a significant discount on our online and live courses.

Integrating MSR into your practice can significantly enhance your clinical practice. The benefits we mentioned are only a few reasons for joining our MSR team.