Mastering Cervical Spine Diagnostics: Anatomy Plus Orthopaedic Examination

- Dr. Brian Abelson

- Mar 30, 2023

- 15 min read

Updated: Dec 5, 2023

"Mastering Cervical Spine Diagnostics: A Guide to Orthopedic Examination" provides an in-depth look at the assessment and evaluation of the cervical spine, an essential component of diagnosing and treating neck pain, injuries, and disorders. As a healthcare professional, understanding the intricacies of cervical spine anatomy and possessing the skills to perform a thorough orthopedic examination is vital for ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

In addition to the detailed anatomical overview, this article offers step-by-step guidance on conducting a comprehensive orthopedic examination of the cervical spine. You'll learn essential techniques for inspection and observation, palpation, and evaluating active and passive ranges of motion. Furthermore, you'll explore various orthopedic tests designed to assess the integrity of the cervical spine's neurological and musculoskeletal components, aiding in the accurate diagnosis.

Article Index:

Part 1 - Cervical Spine Anatomy

Before we dive into the specifics of the cervical spine examination, we must familiarize ourselves with the anatomy, which plays a significant role in its function and the structures involved.

The Osseous Structures – The Bones!

The cervical spine, an integral segment of the vertebral column, encompasses a series of seven vertebrae designated as C1 through C7. These osseous structures offer essential support and facilitate an extensive range of motion for the craniocervical junction and the cervical region. Each vertebra exhibits specific morphological characteristics corresponding to its distinct functional responsibilities within the cervical spine's biomechanical system.

Atlas (C1):

The most superior cervical vertebra

Devoid of a vertebral body and spinous process

Constituted by anterior and posterior arches, connected by bilateral lateral masses

Articulates cranially with the occipital bone, constituting the atlanto-occipital joint

Facilitates the "yes" motion, or sagittal plane movements (flexion and extension) of the head

Axis (C2):

The subsequent cervical vertebra

Distinguished by a prominent, tooth-like protrusion termed the odontoid process (dens), which emanates superiorly from its vertebral body. Establishes a pivot joint with the atlas (C1), permitting axial rotation of the head.

Forms a connection with the atlas via the atlantoaxial joint

Cervical vertebrae (C3 to C7):

Defined by a diminutive, elliptical vertebral body

Exhibit bifurcated spinous processes (excluding C7)

Possess transverse foramina within the transverse processes, accommodating the passage of vertebral arteries and veins.

Zygapophyseal (facet) joints facilitate flexion, extension, and rotation within the cervical region. Intervertebral discs situated between the vertebral bodies of adjacent vertebrae serve as shock absorbers and enable dynamic motion.

Intervertebral Discs

Intervertebral discs, strategically positioned between the vertebral bodies, are essential in maintaining cervical spine mobility and mitigating biomechanical stress. These avascular, fibrocartilaginous structures have an outer annulus fibrosus and an inner nucleus pulposus.

Annulus fibrosus:

Exhibits a multi-lamellar, concentric arrangement of fibrous tissue

Serves to confine and provide structural reinforcement to the viscous nucleus pulposus

Nucleus pulposus:

Comprises a proteoglycan-rich, gelatinous matrix

Facilitates the even distribution of compressive forces throughout the disc and adjacent vertebral endplates, thereby optimizing load transmission and energy dissipation

Muscles

The cervical spine is surrounded by an intricate network of muscles that provide both stability and coordinated motion. These muscles are organized into superficial, intermediate, and deep layers, with each layer containing muscles specifically designed to execute particular functions.

Superficial layer:

Sternocleidomastoid:

Origin: Manubrium of the sternum and medial portion of the clavicle

Insertion: Mastoid process of the temporal bone

Action: Neck flexion and rotation

Innervation: Accessory nerve (CN XI) and cervical plexus (C2-C3)

Trigger point referral pattern: Sternal head trigger points typically cause pain in the forehead near the eyebrows, above the eye towards the temple, in the cheek and upper jaw, and at the back of the head near the occiput. Clavicular head trigger points usually refer pain to areas behind the ear and around the mastoid process, the lower jaw and angle of the jaw, and the anterior neck region close to the throat.

Trapezius:

Origin: External occipital protuberance, nuchal ligament, and spinous processes of C7-T12

Insertion: Lateral third of the clavicle, acromion, and spine of the scapula

Action: Neck extension

Innervation: Accessory nerve (CN XI) and cervical plexus (C3-C4)

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain in the upper neck and base of the skull, which may contribute to tension headaches, as well as pain in the shoulder blade area, and sometimes extending into the upper back and arm. Additionally, trigger points in the lower trapezius can cause discomfort in the mid-back region.

Splenius muscles:

Splenius Capitis:

Origin: Nuchal ligament and spinous processes of C7-T3

Insertion: Mastoid process of the temporal bone and lateral portion of the occipital bone

Action: Neck extension and rotation

Trigger point referral pattern: Trigger points in the splenius capitis muscle can lead to referred pain in different areas of the head and neck. Common referral patterns include pain at the base of the skull, along the back and side of the neck, behind the ear, and occasionally extending to the temple and forehead regions. These trigger points may contribute to tension headaches and neck discomfort.

Splenius Cervicis:

Origin: Spinous processes of T3-T6

Insertion: Transverse processes of C1-C3

Action: Neck extension and rotation

Innervation: Posterior rami of the spinal nerves

Trigger point referral pattern: Trigger points in the splenius cervicis muscle can result in referred pain in various areas of the neck and head. Common referral patterns include pain at the base of the skull, along the back of the neck, and extending to the top of the shoulder. These trigger points can contribute to neck discomfort and stiffness.

Levator Scapulae:

Origin: Posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C1-C4

Insertion: Medial border of the scapula, superior to the root of the scapular spine Action: Elevates scapula and tilts glenoid cavity inferiorly; laterally flexes and rotates neck when the scapula is fixed

Innervation: Dorsal scapular nerve (C5) and cervical nerves (C3 and C4)

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain along the upper part of the shoulder blade, the back and side of the neck, and sometimes extending up to the base of the skull. These trigger points may contribute to neck discomfort, stiffness, and limited range of motion.

Intermediate layer:

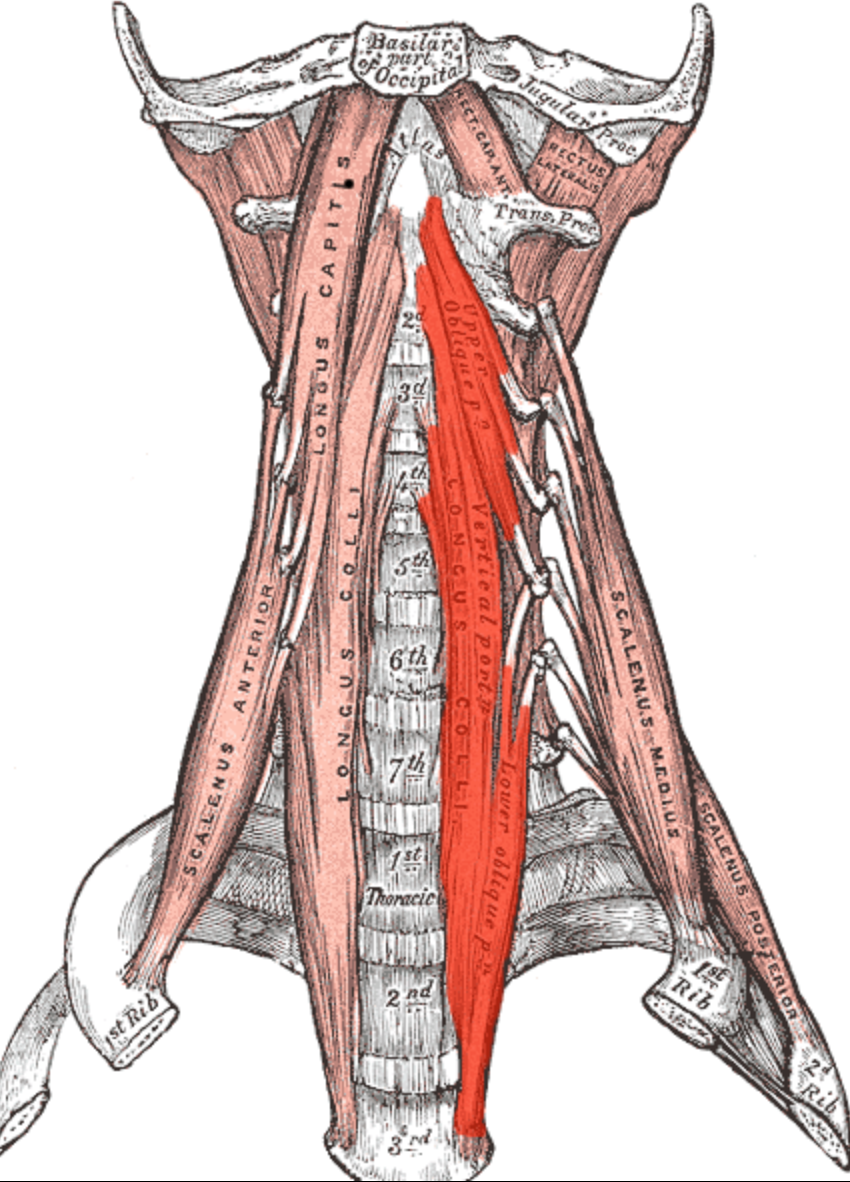

Longus Colli:

Origin: Anterior tubercles of C3-C5 transverse processes, bodies of T1-T3, and anterior surface of T1-T3 vertebral bodies

Insertion: Anterior tubercles of C5-C6 transverse processes and anterior surface of C1-C4 vertebral bodies

Action: Neck flexion and stabilization of the cervical spine

Innervation: Ventral rami of the cervical spinal nerves

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain in the front and side of the neck, sometimes radiating towards the throat, and occasionally extending to the jaw or the back of the head.

Longus Capitis:

Origin: Anterior tubercles of C3-C6 transverse processes

Insertion: Inferior surface of the basilar part of the occipital bone

Action: Neck flexion and stabilization of the cervical spine

Innervation: Ventral rami of the cervical spinal nerves (C1-C4)

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain at the base of the skull, extending along the back of the head, and sometimes radiating to the forehead or temple region.

Deep layer (suboccipital triangle):

Cervical transversospinales muscles:

These muscles consist of the semispinalis cervicis, multifidus, and rotatores cervicis, which are part of the broader transversospinales muscle group.

Semispinalis cervicis:

Origin: Transverse processes of T1-T6 vertebrae

Insertion: Spinous processes of C2-C5 vertebrae

Action: Neck extension, lateral flexion, and contralateral rotation

Innervation: Posterior rami of the cervical spinal nerves

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain at the base of the skull, along the back of the neck, and sometimes extending to the top of the head or behind the ear.

Multifidus Cervical Region:

Origin: Posterior tubercles of the cervical vertebrae, the articular processes of the thoracic vertebrae, and the sacrum

Insertion: Spinous processes of vertebrae 2-4 segments superior to their origin

Action: Stabilization of the vertebral column, extension, and contralateral rotation

Innervation: Posterior rami of the spinal nerves

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain along the back of the neck, near the base of the skull, and occasionally extending to the top of the head or behind the ear.

Rotatores cervicis:

Origin: Transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae

Insertion: Spinous processes of vertebrae 1-2 segments superior to their origin

Action: Stabilization of the vertebral column, extension, and contralateral rotation

Innervation: Posterior rami of the cervical spinal nerves

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain at the base of the skull, along the back of the neck, and occasionally extending to the top of the head or behind the ear.

(Click the above image to go to Dr. Joe Muscolino's site)

Sub-Occipitals

Rectus Capitis Posterior Major and Minor:

Rectus Capitis Posterior Major:

Origin: Spinous process of the axis (C2)

Insertion: Lateral part of the inferior nuchal line of the occipital bone

Action: Extension and rotation of the head

Innervation: Suboccipital nerve (posterior ramus of C1)

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain at the base of the skull, along the back and side of the neck, and occasionally extending up to the back of the head or behind the ear.

Rectus Capitis Posterior Minor:

Origin: Posterior tubercle of the posterior arch of the atlas (C1)

Insertion: Medial part of the inferior nuchal line of the occipital bone

Action: Extension of the head

Innervation: Suboccipital nerve (posterior ramus of C1)

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain at the base of the skull, along the back and side of the neck, and occasionally extending up to the back of the head or behind the ear.

Obliquus Capitis Superior and Inferior:

Obliquus Capitis Superior:

Origin: Transverse process of the atlas (C1)

Insertion: Between the superior and inferior nuchal lines of the occipital bone

Action: Extension, rotation, and lateral flexion of the head

Innervation: Suboccipital nerve (posterior ramus of C1)

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain at the base of the skull, along the back and side of the neck, and occasionally extending up to the back of the head or behind the ear.

Obliquus Capitis Inferior:

Origin: Spinous process of the axis (C2)

Insertion: Transverse process of the atlas (C1)

Action: Rotation of the head and neck

Innervation: Suboccipital nerve (posterior ramus of C1)

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain at the base of the skull, along the back and side of the neck, and occasionally extending up to the back of the head or behind the ear.

Scalene Muscles

The scalene muscles are located in the lateral neck region and are covered by several superficial muscles and soft tissues. Some of the muscles and structures that lie superficial (on top) to the scalenes include:

Platysma: A thin, sheet-like muscle that covers the anterolateral neck region, extending from the collarbone to the lower face.

Sternocleidomastoid (SCM): A large muscle that runs diagonally across the neck from the sternum and clavicle to the mastoid process of the temporal bone. It is located more anteriorly but partially covers the scalene muscles.

Prevertebral fascia: A connective tissue layer separating the scalene muscles from the more superficial ones like the sternocleidomastoid. It is important to note that the scalene muscles are deep neck muscles, so they are not directly overlaid by many other muscles. The aforementioned muscles and fascia are in proximity to the scalenes and may partially cover them, but the scalene muscles are still relatively deep in the neck.

Anterior scalene:

Origin: Anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C3-C6 vertebrae

Insertion: First rib (scalene tubercle)

Action: Neck flexion, lateral flexion, and elevation of the first rib during inspiration

Innervation: Ventral rami of the cervical spinal nerves (C4-C6)

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain along the front and side of the neck, extending into the chest, upper back, and sometimes radiating down the arm, possibly even reaching the thumb and index finger.

Middle scalene:

Origin: Posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C2-C7 vertebrae

Insertion: First rib (posterior to the scalene tubercle)

Action: Neck flexion, lateral flexion, and elevation of the first rib during inspiration

Innervation: Ventral rami of the cervical spinal nerves (C3-C8)

Tigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain along the side of the neck, extending into the upper back, shoulder blade, and sometimes radiating down the arm, possibly reaching the thumb, index, and middle fingers

Posterior scalene:

Origin: Posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of C4-C6 vertebrae

Insertion: Second rib (external surface)

Action: Neck flexion, lateral flexion, and elevation of the second rib during inspiration

Innervation: Ventral rami of the cervical spinal nerves (C5-C8)

Trigger point referral pattern: Common referral patterns include pain along the side and back of the neck, extending into the upper back, shoulder blade, and sometimes radiating down the arm, possibly reaching the thumb, index, and middle fingers.

Ligaments

The cervical spine is reinforced by a network of critical ligaments that collaboratively maintain spinal stability and safeguard neural structures. These ligaments comprise:

Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL):

Location: Extends vertically along the anterior surface of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs

Function: Restricts spinal extension and contributes to maintaining the integrity of intervertebral discs

Posterior Longitudinal Ligament (PLL):

Location: Stretches vertically along the posterior surface of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs, situated within the vertebral canal

Function: Constrains spinal flexion and supports the intervertebral discs in withstanding posteriorly directed forces

Ligamentum Flavum:

Location: Bridges the laminae of adjacent vertebrae, forming the posterior wall of the vertebral canal

Function: Preserves vertebral column stability, assists in averting excessive spinal flexion, and contributes to spinal column elasticity

Interspinous Ligaments:

Location: Connect the spinous processes of adjacent vertebrae

Function: Impart stability and delimit spinal flexion

Capsular Ligaments:

Location: Encapsulate the facet (zygapophyseal) joints

Function: Stabilize the facet joints and curtail excessive joint movements in all planes

Neuroanatomy of the Cervical Spine

The cervical spine houses nerve roots that arise from the spinal cord and exit via the intervertebral foramina between each vertebra. These nerve roots contribute to the formation of the cervical and brachial plexuses, which innervate the head, neck, shoulders, and upper limbs, facilitating both motor and sensory functionality.

Cervical Nerve Roots:

Location: Emanate from the spinal cord through the intervertebral foramina between each cervical vertebra

Function: Convey motor and sensory information between the spinal cord and the upper extremities

Morphology: Dorsal and ventral nerve rootlets coalesce to form the spinal nerves

Cervical Plexus:

Formation: Constituted by the anterior rami of spinal nerves C1 through C4

Function: Supplies sensory innervation to the skin of the head, neck, and upper part of the shoulders; motor innervation to several neck muscles, such as the geniohyoid, thyrohyoid, and infrahyoid muscles; and contributes to the formation of the phrenic nerve (C3-C5), which innervates the diaphragm

Anatomical Landmarks: Positioned deep within the neck, posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and anteromedial to the levator scapulae and middle scalene muscles

Brachial Plexus:

Formation: Comprised of the anterior rami of spinal nerves C5 through T1

Function: Innervates the upper limbs, providing both motor and sensory function

Anatomical Landmarks: Situated in the neck and axillary regions, coursing between the anterior and middle scalene muscles and extending into the axilla, where it forms multiple terminal branches

Compression or irritation of these nerve roots, commonly referred to as cervical radiculopathy, may manifest as pain, numbness, or weakness in the distribution of the affected nerve.

Vascular Structures of the Cervical Spine

The cervical spine is supplied by a sophisticated network of arteries and veins that ensure the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the spinal cord and surrounding structures. Key vascular structures include:

Vertebral Arteries:

Location: Ascend through the transverse foramina of the cervical vertebrae

Function: Provide blood supply to the cervical spine and posterior portion of the brain

Anatomical Landmarks: Originate from the subclavian arteries and unite at the base of the skull to form the basilar artery

Carotid Arteries:

Function: Crucial for maintaining adequate blood flow to the cervical spine and associated neural structures. Types:

External Carotid Arteries: Supply blood to the face, scalp, and neck muscles

Internal Carotid Arteries: Supply blood to the brain and the eyes

Anatomical Landmarks: Branch from the common carotid arteries at the level of the superior border of the thyroid cartilage

Part 2 - Cervical Examination - Orthopedic Testing

In this video, Dr. Evangelos Mylonas DC demonstrates a comprehensive examination of the cervical spine. He guides you through inspection and observation, palpation, active and passive ranges of motion, and orthopedic examination of the cervical spine. Upon completing this video, you'll gain a deeper understanding of the various components involved in a thorough cervical examination and the importance of each step in the assessment process.

After the video, the rest of this article summarizes the key topics discussed, emphasizing the crucial elements of an orthopedic evaluation of the cervical spine.

Critical aspects of the cervical examination:

Patient history:

At the onset of the examination, the healthcare provider will systematically collect the patient's medical history, emphasizing any antecedent injuries, surgical interventions, or medical conditions pertinent to the cervical spine. This step is vital as it equips the provider with insights into potential etiologies of the patient's symptoms and guides the subsequent evaluation process.

Visual inspection:

During this phase of the cervical examination, the healthcare provider will meticulously inspect the neck and spine for discernible abnormalities, such as edema, deformity, or asymmetry. Particular attention is given to the patient's posture and spinal alignment, in addition to any indications of muscle atrophy, cutaneous discoloration, or other anomalous findings.

Range of motion assessment:

Throughout the examination, the healthcare provider will appraise the patient's cervical spine range of motion by monitoring their head and neck movements across multiple planes:

Flexion: 80-90 degrees

Extension: 70 degrees

Lateral Flexion: 20-45 degrees

Rotation: 70-90 degrees

Palpation:

This tactile examination aims to discern any:

Tenderness: Evaluating for pain or discomfort along the cervical vertebrae, paraspinal musculature, and associated ligamentous structures

Swelling: Investigating for manifestations of inflammation or edema within the cervical spine region

Abnormalities: Identifying any irregularities, such as osseous deformities, myospasms, or asymmetries in the cervical spine and adjacent anatomical structures

Special Tests:

Spurling's (Neck Compression) Test:

Procedure: The patient is seated, and the provider laterally flexes the patient's head toward the symptomatic side, subsequently applying axial compression.

Purpose: This test evaluates cervical radiculopathy by reproducing the patient's symptoms via foraminal narrowing.

Sensitivity: 30-60%, Specificity: 90-100%

Bakody Sign:

Procedure: The patient positions their hand on the affected side atop their head.

Purpose: A positive Bakody Sign indicates alleviation of pain or paresthesia, suggesting cervical radiculopathy or nerve root irritation.

Sensitivity & Specificity: Variable

Distraction Test:

Procedure: With the patient seated, the provider places one hand under the patient's chin and the other on the occiput, gently lifting to distract the cervical spine.

Purpose: A positive test, signified by symptom relief, suggests cervical radiculopathy.

Sensitivity: 44%, Specificity: 94%

Shoulder Depression Test:

Procedure: The provider laterally flexes the patient's head to the unaffected side while applying downward pressure on the ipsilateral shoulder.

Purpose: A positive test, denoted by pain or paresthesia, indicates nerve root tension or adhesions.

Sensitivity & Specificity: Variable

Lhermitte's Test:

Procedure: The patient is seated with their neck flexed forward, and the provider taps the spine with a reflex hammer.

Purpose: A positive test, characterized by radiating pain or electric shock-like sensations, may suggest cervical myelopathy or multiple sclerosis.

Sensitivity: 16-65% and Specificity: 60-97%

Valsalva Maneuver:

Procedure: The patient inhales deeply and bears down as if straining during a bowel movement.

Purpose: A positive test, indicated by an increase in pain, suggests heightened intrathecal pressure, potentially indicative of a space-occupying lesion or disc herniation.

Sensitivity: 32% and Specificity: 87%

Conclusion

Mastering Cervical Spine Diagnostics: A Guide to Orthopedic Examination" offers an extensive exploration of cervical spine assessment and evaluation, which is crucial for diagnosing and treating neck pain, injuries, and disorders. As a healthcare professional, it is essential to grasp the complexities of cervical spine anatomy and be proficient in conducting thorough orthopedic examinations for optimal patient outcomes.

This article presents an overview and provides step-by-step instructions for performing a complete orthopedic examination of the cervical spine. You'll gain valuable insights into crucial techniques for inspection and observation, palpation, and assessing active and passive ranges of motion. Additionally, you'll discover various orthopedic tests to evaluate the cervical spine's musculoskeletal integrity, facilitating an accurate diagnosis.

DR. BRIAN ABELSON DC. - The Author

Dr. Abelson's approach in musculoskeletal health care reflects a deep commitment to evidence-based practices and continuous learning. In his work at Kinetic Health in Calgary, Alberta, he focuses on integrating the latest research with a compassionate understanding of each patient's unique needs. As the developer of the Motion Specific Release (MSR) Treatment Systems, he views his role as both a practitioner and an educator, dedicated to sharing knowledge and techniques that can benefit the wider healthcare community. His ongoing efforts in teaching and practice aim to contribute positively to the field of musculoskeletal health, with a constant emphasis on patient-centered care and the collective advancement of treatment methods.

Revolutionize Your Practice with Motion Specific Release (MSR)!

MSR, a cutting-edge treatment system, uniquely fuses varied therapeutic perspectives to resolve musculoskeletal conditions effectively.

Attend our courses to equip yourself with innovative soft-tissue and osseous techniques that seamlessly integrate into your clinical practice and empower your patients by relieving their pain and restoring function. Our curriculum marries medical science with creative therapeutic approaches and provides a comprehensive understanding of musculoskeletal diagnosis and treatment methods.

Our system offers a blend of orthopedic and neurological assessments, myofascial interventions, osseous manipulations, acupressure techniques, kinetic chain explorations, and functional exercise plans.

With MSR, your practice will flourish, achieve remarkable clinical outcomes, and see patient referrals skyrocket. Step into the future of treatment with MSR courses and membership!

References

Abelson, B., Abelson, K., & Mylonas, E. (2018, February). A Practitioner's Guide to Motion Specific Release, Functional, Successful, Easy to Implement Techniques for Musculoskeletal Injuries (1st edition). Rowan Tree Books.

Boyles, R. E., Walker, M. J., & Young, B. A. (2011). The Sensitivity and Specificity of the Slump and the Straight Leg Raise Tests in Patients with Lumbar Disc Herniation. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 41(4), 242-248.

Clarkson, H. M. (2000). Musculoskeletal Assessment: Joint Motion and Muscle Testing (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Côté, P., Cassidy, J. D., & Yong-Hing, K. (1997). The Validity of the Extension-Compression Test as a Clinical Evaluation Procedure for Patients with Neck Pain. Spine, 22(9), 977-984.

Dutton, M. (2012). Dutton's Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Gray, H., Standring, S., & Ellis, H. (2008). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (40th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone.

Hammer, W. I. (2007). Functional Soft-Tissue Examination and Treatment by Manual Methods (3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Hertling, D., & Kessler, R. M. (2006). Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders: Physical Therapy Principles and Methods (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Kendall, F. P., McCreary, E. K., & Provance, P. G. (1993). Muscles: Testing and Function, with Posture and Pain (4th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

Magee, D. J. (2014). Orthopedic Physical Assessment (6th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders.

Neumann, D. A. (2017). Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation (3rd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Prentice, W. E. (2017). Principles of Athletic Training: A Guide to Evidence-Based Clinical Practice (16th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Disclaimer:

The content on the MSR website, including articles and embedded videos, serves educational and informational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice; only certified MSR practitioners should practice these techniques. By accessing this content, you assume full responsibility for your use of the information, acknowledging that the authors and contributors are not liable for any damages or claims that may arise.

This website does not establish a physician-patient relationship. If you have a medical concern, consult an appropriately licensed healthcare provider. Users under the age of 18 are not permitted to use the site. The MSR website may also feature links to third-party sites; however, we bear no responsibility for the content or practices of these external websites.

By using the MSR website, you agree to indemnify and hold the authors and contributors harmless from any claims, including legal fees, arising from your use of the site or violating these terms. This disclaimer constitutes part of the understanding between you and the website's authors regarding the use of the MSR website. For more information, read the full disclaimer and policies in this website.

Comments